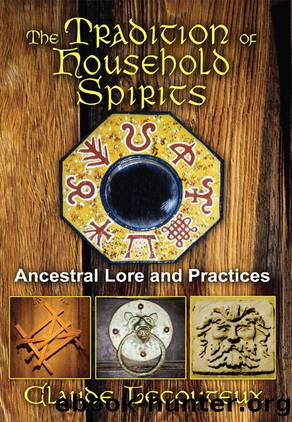

The Tradition of Household Spirits by Claude Lecouteux

Author:Claude Lecouteux

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Spirituality/Folklore

Publisher: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Published: 2002-01-02T00:00:00+00:00

Dwarf as housekeeper, Haslach (Germany), twentieth century (photograph by C. Lecouteux)

The Spirits and the Dead

âThe first dead inhabitant can change into a house spirit,â notes Martti Haavio for Finland. Hans F. Feilberg confirms this for the Scandinavian countries, but Lauri Honko notes that this is never the case in à ngermanland.19 Eugène Rolland cites a testimony from Finistère in Brittany that says: âThe sprites of the stables are former farmhands. When still alive, they neglected the horses entrusted to them; after they died, they were condemned to take care of them.â20 Throughout my research I have been continually come across clues that imply a close connection between the domestic spirit and the dead man. Eventually, this caught my attention and posed new questions. Letâs now examine some of the more significant traces.

Among the Wallachians, the zimt is the feast of the household godsâeach hearth has oneâand the ancestors. The house is cleaned, the table set, friends are invited, and the memory of the departed is also celebrated at this time. These deceased are invited to sit at the table where there are empty chairs reserved for them.21

In Bulgaria, at the Feast of the Dead, offerings are placed in the hearth while saying: âRejoice, master of the house,â22 In Germany, the souls of the dead intentionally remain close to the furnace, the habitual residence for spirits, while in Switzerland, traditions collected at the beginning of the twentieth century by Josef Müller in the canton of Uri, tell us that souls in torment stay, in front of, behind, or inside the stove.23 The dead also live in the doors24 and in the block of wood forming the lintel, and the following is asserted:

Someone who knocks down an old house in the Schächental (Uri) and builds a new one, should never take the lintel block, which should have holes bored into it, otherwise the spirits and misfortune of the demolished house will enter the new one.25

In Estonia, Jacob Grimm informs us that âfood for the dead is left on the floor of one room. The master of the house enters there late in the evening with a long torch and urges them to eat, calling them by name. Some time later, when he thinks they have eaten their fill, he commands them, while breaking his torch on the lintel, to return whence they came and to avoid stepping upon their robes while returning. If the harvest was poor, it was attributed to the poor hospitality shown the souls of the dead.â26 It so happens that this rite matches the one intended to propitiate the house spirits. Almost everywhere, the spirit behaves like a âwhite ladyâ (banshee) and heralds the death of the master of the house.27 It is often confused with the rapping spirit (poltergeist) who is most often a dead person who reveals his or her presence by various noises.28

The sixteenth-century Zimmern Chronicle states, when speaking of erdemenle and wichtenmendle: âMany believe they are men who were once cursed and hope to find

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Ancient & Controversial Knowledge | Ghosts & Hauntings |

| Hermetism & Rosicrucianism | Magic Studies |

| Occultism | Parapsychology |

| Supernatural | UFOs |

| Unexplained Mysteries |

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4473)

Sigil Witchery by Laura Tempest Zakroff(4246)

Real Magic by Dean Radin PhD(4129)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(4004)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3640)

Journeys Out of the Body by Robert Monroe(3624)

Alchemy and Alchemists by C. J. S. Thompson(3522)

The Rosicrucians by Christopher McIntosh(3520)

Mysteries by Colin Wilson(3454)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3343)

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika (Translated) by Svatmarama(3342)

Wicca: a guide for the solitary practitioner by Scott Cunningham(3178)

John Dee and the Empire of Angels by Jason Louv(3166)

Infinite Energy Technologies by Finley Eversole(2984)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2939)

Dark Star Rising by Gary Lachman(2867)

The Book of Lies by Aleister Crowley(2846)

Aliens by Jim Al-Khalili(2829)

To Light a Sacred Flame by Silver RavenWolf(2823)